“He was one of the twentieth century’s most famous atheist, his daughter became a Christian.”

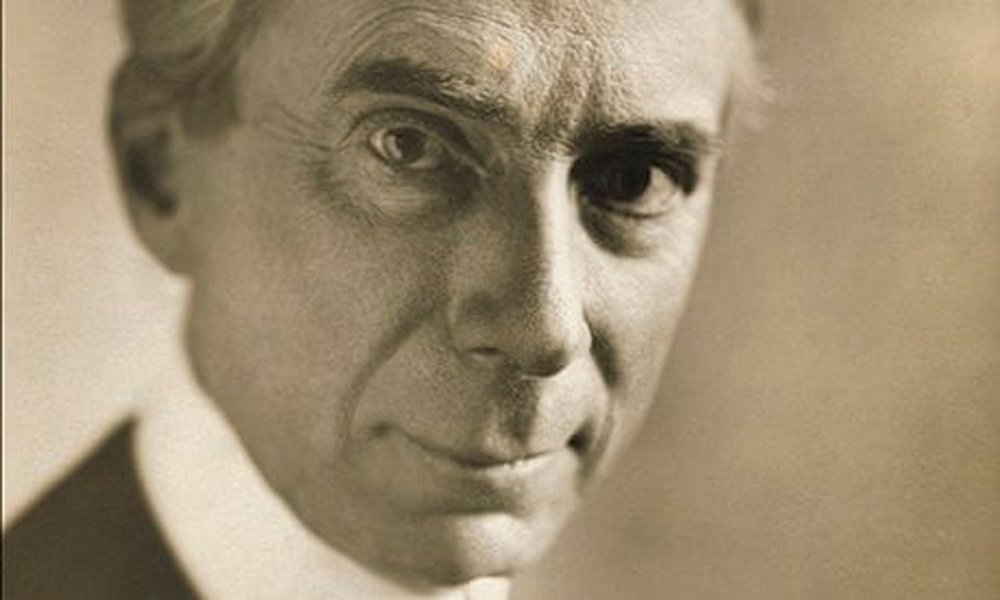

A British mathematician and philosopher, Bertrand Russell (1872 to 1970) were admired as one of the visionary thinkers worldwide.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1959 on the basis that he was “a defender of humanity and freedom of thought.”

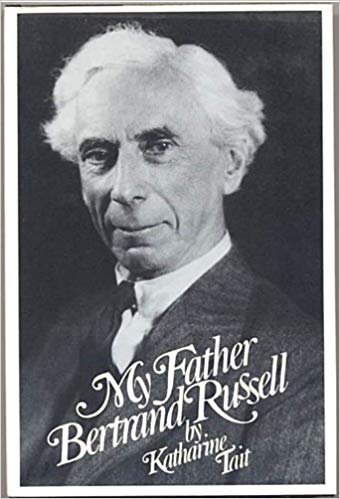

A friend recently suggested that I collect a copy of My Father, Bertrand Russell that his daughter Katharine Tait wrote in 1975.

It was quite interesting.

She begins by remembering her earliest history in London and ends the book with the following words:

“He was the most fascinating man I have ever known, the only man I ever loved, the greatest man I shall ever meet, the wittiest, the gayest, the most charming. It was a privilege to know him, and I thank God he was my father.”

Several years ago, while browsing in a bookstore in the east, a book with Russell’s photograph on the dust cover caught my eye.

The title was My Father-Bertrand Russell, by Katharine Tait.

The only child of Russell was Katharine Tait. Born in London in 1923, she pursued a training course at her parents’ innovative school in Beacon Hill.

It was a small academy devoted to promoting ‘ free-thinking, ‘ that is to say, atheist humanism.

The writer attempts in this fascinating book to describe what it was like having Bertrand Russell for a father.

It is not a beautiful image.

One, who loved Russell with passion, although not always agree with him, gives the following glimpses into Russell’s life and lessons.

Atheist Chinese Computer Engineer Finds Jesus After Reading The Bible

Although, she writes the book with pure love and affection for her father. In her life, she also discovers some interesting contradictions.

Here are a great five memorable quotes from her. I hope you’ll get a copy of the book and read it for yourself.

“Christians were mocked for imagining that man is important in the vast scheme of the universe,

even the high point of all creation–and yet my father thought man and his preservation the most important thing in the world, and he lived in hopes of a better life to come” (p. 184).

“My father did not intend his education to be propaganda; he always wanted us to consider both sides and then make up our minds. ‘

Considering both sides’ meant hearing the opinions on both sides as well as studying the facts…In practice, at Beacon Hill, ‘making up our own minds’ usually meant agreeing with my father…There was never a cogent presentation of the Christian faith, for instance, from someone who believed in it” (p. 94).

“I doubt if my father ever believed in behaviorism quite as thoroughly as he appears to in his book on education;

he was far too much the passionate moralist. He may have thought that the right conditioning of his children would produce the right kind of people, but he certainly didn’t consider himself the inevitable result of his conditioning” (p. 62).

“My father was a feminist too, of course. His parents had been feminists, his first wife a feminist,

he had campaigned for women’s votes long before it was fashionable. But feminism did not mean the same to him as to my mother.

He was willing to treat her with absolute respect grant her every possible privilege, but he wanted her to make being his wife her career, and it was not a career she would have chosen for herself” (p. 50).

“Somewhere at the back of my father’s mind at the bottom of his heart, in the depths of his soul, there’s an empty space that had once been filled by God, and he never found anything else to put in it. He wrote of it in letters during the First World War, and once he said that human affection was to him ‘at the bottom at attempt to escape from the vain search for God’” (p. 185).

END.

SOURCE: Christiancourier